South Africa is the first African country to debate the WHO’s I.H.R 2005 amendments and proposed new pandemic treaty in Parliament

WHO's monopoly over health is a national elections issue for every country. Proper public participation and an amendment to Constitutions are imperative. Please sign the petition at the end to support

By Shabnam Palesa Mohamed

On the first of March 2024, the first debate on the WHO facilitated IHR 2005 amendments and proposed new pandemic treaty was heard in South Africa’s parliament during a dedicated mini plenary session. This comes after almost three years of advocacy by local activists, alongside activists in other countries, ahead of a World Health Assembly vote on these controversial instruments, this May.

The plenary debate was introduced by ACDP MP Steve Swart, supported by fellow MP Wayne Thring. Parliamentarians representing other political parties also spoke, giving their views on the role of the WHO, its performance during Covid-19, the need for pandemic preparedness, these two international instruments, S231 of the South African constitution, and lastly, the imperative role of public participation.

The Freedom Charter, adopted at the Congress of The People in 1955, declared that “(t)he People shall govern”. It is a foundational value that government is government by the people and this value is also enshrined in section 42(3) of our Constitution which states in S.42(3): The National Assembly is elected to represent the people and to ensure government by the people under the Constitution. It does this by choosing the President, by providing a national forum for public consideration of issues, by passing legislation and by scrutinizing and overseeing executive action.

All parties interested in or affected by legislation must be given a real opportunity to have their say, to know they are taken seriously as citizens, and that their views matter and will receive due consideration. All legislation must conform to the Constitution in terms of both content and the manner in which it is adopted. The obligation to facilitate public participation is a material part of the law-making process. A reasonable opportunity must be offered to the public and all interested parties to know about the proposed issues and to have an adequate say.

Over December 2023, I worked with the ACDP to counter these WHO facilitated intruments. The ACDP sent a formal letter I co-drafted to the WHO, rejecting amendments to the IHR 2005, which would shorten the amount of time member states have to respond to further amendments. A summary of this action can be found here. The letter includes the fact that the IHR 2005 was never domesticated, rendering IHR 2005 any and all subsequent amendments null and void in the law.

Also in December, I raised S.231 of the South African constitution as a counter to the WHO facilitated power grab. During the parliamentary debate last Friday, the ACDP called for Section 231 of South Africa’s constitution to be amended, to ensure certainty on parliamentary oversight in all international agreements. Section 231 of the South African Constitution currently states:

International agreements

231. (1) The negotiating and signing of all international agreements is the responsibility of the national executive.

(2) An international agreement binds the Republic only after it has been approved by resolution in both the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces, unless it is an agreement referred to in subsection (3).

(3) An international agreement of a technical, administrative or executive nature, or an agreement which does not require either ratification or accession, entered into by the national executive, binds the Republic without approval by the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces, but must be tabled in the Assembly and the Council within a reasonable time.

(4) Any international agreement becomes law in the Republic when it is enacted into law by national legislation; but a self-executing provision of an agreement that has been approved by Parliament is law in the Republic unless it is inconsistent with the Constitution or an Act of Parliament.

(5) The Republic is bound by international agreements which were binding on the Republic when this Constitution took effect.

I was asked by the ACDP for time constrained input, contributing to a very short speaking time allocated to ACDP and other political parties. I raised the unilateral power given to the WHO’s director general to declare a national pandemic as a geo-political weapons, like sanctions. The ADCP sent its detailed debate statement to me. Both these documents can be reviewed below.

It is imperative to remember the role of the African bloc in standing up to the WHO facilitated power grab, as far back as 2022 at World Health Assembly 75. While much more must be done to educate the public, politicians, lawyers and health care workers, South Africa continues to have an impact in international human rights law, defending health, freedom and sovereignty. It appears inevitable that we will need to approach our courts to interdict our WHO representative from voting at World Health Assembly in May, and to interdict the unlawful adoption of these two instruments.

Contribution to WHO debate in SA Parliament

Brief memo drafted by Shabnam Palesa Mohamed

1. In 2022, the 47 nation African bloc took a historic stand at World Health Assembly 75 because amendments to the International Health Regulations 2005 were rushed, not inclusive, and posed a risk to sovereignty. The status quo remains, but added to the danger we face as Africans is a new pandemic accord or treaty, which the Hon. Minster Pandor, in 2022, promised would go through a parliamentary approval process. With 2 months ahead of a catastrophic vote at the World Health Assembly this May, the ACDP, like politicians and the public in India, Chile, Slovakia, New Zealand, U.S, UK and others, raises an urgent alarm.

2. Apart from failures on opiod, nuclear, tobacco and a manufactured H1N1 scare, the WHO is riddled with conflicts of interest from funding by Big Pharma, billionaires, and influential member states; mismanagement; corruption and allegations of racism. Moreover, WHO workers committed crimes of sexual exploitation against women of the DRC. During Covid-19, the WHO’s recommendations were not only scientifically flawed, but lead to fundamental violations of our Constitution, and international human rights law.

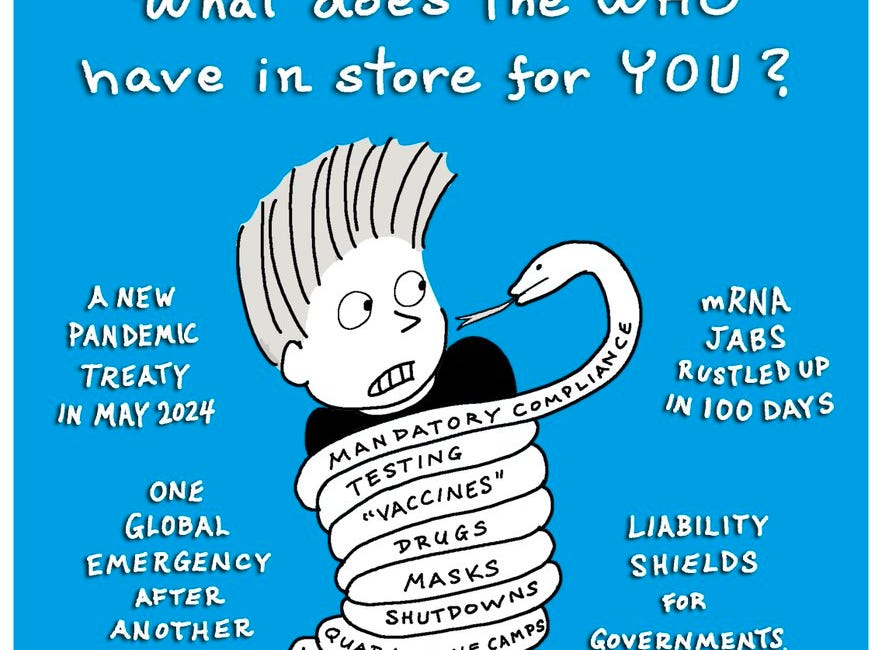

3. Some disturbing articles in aforementioned controversial instruments include:

Giving WHO’s Director-General the power to unilaterally declare a public health emergency in any country, without the country’s agreement. This is dangerous geo-political tool that can be wielded against us or any African and other nation.

Whether a real or potential health emergency, that targeted country would have a mere 48 hours to respond to the WHO or explain its decisions, or face the consequences. WHO is on record talking about sanctions to enforce compliance.

The WHO. through member states, is also calling for pathogen sharing, which needs dangerous bio labs, where risky gain of function experiments can and will happen, reminding us Africans of the days of apartheid and biological experiments.

Censorship of the right to free speech and dissent, and the eradication of the terms dignity, human rights and freedom. These terms violate our Bill of Rights.

Giving WHO power to require states to enforce mandatory pharmaceutical products, like vaccines, and forced quarantine where people becomes prisoners.

4. Where is the parliamentary oversight? These dangerous articles become binding if we do not reject them. Among other parties, politicians and civil society members from other countries, ACDP wrote to the WHO in December, objecting to secretive IHR amendments. Still, the WHO recently held a sham public participation process in which only 11 – 19 member states attended. An expert witness reports that South Africa was not represented.

5. There are two key obstacles to the IHR amendments and pandemic treaty/accord being voted into effect in May. The first is robust disagreement between states worried about what funding will be expected, and what loans will be needed. The other is resistance by civil society that lead to debates in, for eg, the UK parliament. Given that we are months away from a national election, the ACDP places on record its public interest request for:

a) A 2022 PAIA filed by THJ, on these two instruments, to be responded to urgently

b) A presentation by a panel of civil society experts, who have no conflicts of interest

c) A robust parliamentary discussion process, followed by a vote, ahead of May 2024

d) A comprehensive public education and participation process including a referendum

South Africa has allies in Africa and internationally. We do not need to suffer the pain, suffering, and trauma of a WHO lead campaign again.

B. ACDP statements on WHO facilitated IHR amendments and new pandemic treaty

SPEECH ON ACDP SUBJECT FOR DISCUSSION (S. N. SWART) PARLIAMENT'S ROLE IN TERMS OF SECTION 231(2) OF THE CONSTITUTION, WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION'S PROPOSED PANDEMIC AGREEMENT AND AMENDMENTS TO THE INTERNATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS OF 2005.

STEVEN SWART, ACDP MP 1 MARCH 2024

Chairperson, the ACDP fully appreciates that the negotiating and signing of all international agreements is the responsibility of the national executive as set out in section 231(1) of the Constitution.

However, section 231(2) states that an international agreement binds the Republic only after it has been approved by resolution in both the National Assembly and the NCOP, unless it is an agreement referred to in subsection (3) of a technical, administrative or executive nature (which does not require either ratification of accession).

Agreements requiring parliamentary approval are agreements which require ratification or accession (usually multilateral agreements); have financial implications which require an additional budgetary allocation from Parliament; or have legislative or domestic implications (eg. require new legislation or legislative amendments).

While parliament’s approval process is clearly set out in section 231 (2), the ACDP is concerned about the time Parliament takes to consider and approve international agreements. I have also never seen Parliament amend an agreement tabled before it. Surely Parliament is not just a rubber stamp for such agreements?

Because of this delay between the signing and ratification by parliament, I submit that Parliament has, over and above its powers in terms of section 231(2) also an oversight function in terms of section 55(2) over the Executive.

The question is when there is uncertainty as to whether parliament will be required to approve amendments to an international agreement it can exercise its powers in terms of section 55(2), particularly when those amendments may threaten the national sovereignty of a member state.It is against this background that we would like to consider the Pandemic Treaty and International Health Regulations 2005 Amendments – both instruments of international law.

The protracted Covid-19 lockdown severely constrained our personal freedoms, and resulted in the closure of tens of thousands of businesses. An estimated 2 million South Africans lost their jobs as a result, joining the ranks of those already struggling and living below the poverty line. Sadly, many have not been able to find sustainable employment since then. In addition, tens of thousands of people are still suffering from Covid-19 vaccine injuries, with little or no recourse to effective medical treatment or compensation. We also saw the gross abuses in the procurement of PPE’s – tens of billions of rands. This past week saw the Special Tribunal found that a R113million PPE contract by the Health Department was invalid.

Countries across the world have been asking questions and even having full parliamentary inquiries into how their governments handled the Covid-19 pandemic – and what role did multinational pharmaceutical companies play in influencing governments and the World Health Organisation.

We as parliamentarians now know how our government was bullied into signing Covid-19 contracts with global Western pharmaceutical manufacturers and suppliers and paid billions of rands for Covid-19 vaccines on highly unfavourable terms in which the manufacturers of the experimental drug acknowledged “that the long term effects and efficacy of the vaccine are not currently known and that there may be adverse effects of the vaccine that are currently not known.” Despite this acknowledgement, government agreed to “indemnify, defend and hold harmless” certain manufacturers from any claims resulting from the vaccine, and was obliged to set up a R250 million Vaccine Injury No-Fault Compensation Scheme.

So what are we dealing with in terms of international law. The first concerns far-reaching amendments to the existing International Health Regulations 2005, and the second is the WHO’s new pandemic treaty, which would support the bureaucracy and financing of the expanded IHR.

Both instruments are, in our view, very concerning as they are designed to transfer binding decision-making powers to the WHO. While the aim of improving how the world prevents and better prepares for disease outbreaks is laudable, what is being proposed will in our view have a huge and detrimental impact on all parts of society and on our country’s sovereignty. It is nothing less than a power grab by the WHO.

The ACDP believes that the proper role of the WHO is to provide information to governments across the globe. Those governments can then decide for themselves what recommendations they like, what they don’t like. It is not to dictate to countries how they should respond to health emergencies, but to partner with and assist such countries.

We are concerned that the WHO is beholden to certain countries, multinationals and powerful individual donors, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. He who pays the piper calls the tune.

The Pandemic Treaty or Agreement must, we believe, be tabled for Parliament’s approval in terms of section 232(2). Indeed, International Relations and Cooperation Minister Pandor of DIRCO has previously said in parliament said that the Pandemic Treaty will be tabled in Parliament for approval - as is required.

Of greater concern are the amendments to the International Health Regulations 2005 being negotiated as we speak. The ACDP is grateful that African countries, led by Botswana, objected to the push by the US to reform these health rules in 2022.

Despite these objections, significant amendments were pushed through at the World Health Assembly on 22 May 2022. Those amendments come into force under international law for all member states within 24 months—that is, by 31 May 2024 - without any oversight or approval from us as parliamentarians. This is concerning.

In response to the US push to reform health rules, 300 further amendments were tabled by unhappy member states. These have been the subject of negotiations and have been debated in various parliaments – but not here in South Africa. South Africa passed the International Health Regulations Act 28 of 1974 as amended by sections 46 and 47 of the Transfer of Powers and Duties of the State President Act,1986, (Act No 97 of 1986). In terms of section 231(5), South Africa “is bound by international agreement which were binding on the Republic when the Constitution took effect” (in 1996).

The International Health Regulations (2005), were adopted by the 58th World Health Assembly on 23 May 2005 and entered into force on 15 June 2007. What is interesting is that the International Health Regulations Bill, 2013, was published for comment in the South African Government Gazette (Notice 36931) on 14 October 2013 in terms of the constitutionally required public consultation process. This Bill sought to repeal the International Health Regulations Act 28 of 1974; to incorporate the International Health Regulations 2005 into South African domestic law in terms of section 231(4) of the Constitution in order to apply the International Health Regulations in South Africa and to provide for the matters connected therewith.

As far as we are aware, this Bill was not passed by the South African Parliament, which brings the domestication of the International Health Regulations 2005 into South African law in terms of the Constitution, and any future purported amendments to the IHR 2005 into question. Alternatively, it means that the International Health Regulations still fall under the ambit of the 1974 Act.

Why should we be concerned?

Despite statements to the contrary, if one reads the amendments together, they will undermine South Africa’s sovereign right to determine its own public health policies. Vague definitions of “health” could allow the WHO to declare pandemics, even permanent pandemics, and allow it to impose binding restrictions such as lockdowns, surveillance and even mandatory treatments on countries. These measures are far-reaching and demand the attention of us not only as law makers, but also in exercising oversight over the executive during negotiations.

We need to be mindful that the WHO (report of the Review Committee regarding amendments to the International Health Regulations, 2005) stated on 6 February 2023 that “the sovereignty of states parties remain foundational to the Regulations. As with the revisions nearly 20 years ago that led to the International Health Regulations (2005), proposed amendments to them will need careful balancing between a State party’s sovereign right to take actions necessary to protect its population against a public health risk, while recognising their mutual vulnerabilities and responsibilities, and the imperative of international cooperation and solidarity, which are key enablers of effective Regulations.”

This is in itself a warning that the sovereign rights of states parties may be compromised.

A South African petition raising awareness gained the support of more than 12 000 people, but has largely been ignored. Why should we be concerned. The proposed amendments significantly change what was previously the “recommendations” to binding requirements through three mechanisms.

The first is the removal the term “non-binding” from article 1 resulting in certain recommendations now becoming binding on member states. We as parliamentarians should all be deeply concerned by the removal of the word “non-binding”. There is much in the existing IHR that would suspend fundamental human and bioethical rights. As article 18 makes clear, these include multiple actions directly restricting fundamental human and bioethical rights, such as requirements for vaccinations and medical examinations, and implementing quarantine or other health measures for suspect persons—in other words, mandates and lockdowns.

Given that South Africa had one of the longest and harshest government imposed lockdowns, we need to be extra cautious in giving these powers to an unelected and unaccountable organisation that is backed by powerful Governments, donors and institutions, and financial mechanisms, including the IMF (International Monetary Fund), the World Bank.

The second is the insertion under new article 13A of the phrase that “Member States” will “undertake to follow WHO’s recommendations” and recognise WHO not as an organisation under the control of countries, but as the “co-ordinating authority of international public health response during public health Emergency of International Concern…”

(New article 13A states: “States Parties recognize WHO as the guidance and coordinating authority of international public health response during public health Emergency of International Concern and undertake to follow WHO’s recommendations in their international public health response.”). It is thus likely to make opposition from lower-income countries extremely difficult to sustain, but we understand that there is a significant push –back from developing countries in the run-up to the vote at the World Health Assembly in May this year.

Thirdly, under article 42, “State Parties” undertake to enact what previously were merely recommendations, without delay, including alarmingly requirements of WHO regarding non-state entities ie the private sector under their jurisdiction. Article 42 states: “Health measures taken pursuant to these Regulations, including the recommendations made under Article 15 and 16, shall be initiated and completed without delay by all State Parties, and applied in a transparent, equitable and non-discriminatory manner. State Parties shall also take measures to ensure Non-State Actors operating in their respective territories comply with such measures.”

“Non-State Actors” means private businesses, charities, and individuals. In other words, everyone and everything comes under the control of the WHO, once the director general declares a public health emergency of international concern. Where these were merely recommendations, they now become binding on member- states. What makes it worse is that we as MPs have no say over these fundamental changes to the IHR – which may threaten our countries sovereignty over public health issues.

Furthermore, articles 15 and 16 mentioned here, allow the WHO to require a state to provide resources, “health products, technologies and know how” and to allow the WHO to deploy “personnel” into the country—that is, it will have control over entry across national borders for whoever it chooses. The WHO also repeats the requirement for the country to require the implementation of “medical countermeasures”—testing, vaccines, quarantine—on their population where the WHO demands it.

These proposed amendments taken together are very far-reaching and will, we believe, empower the WHO to issue requirements or obligations to South Africa to mandate highly restrictive measures, such as lockdowns, masks, quarantines, travel restrictions and medication of individuals, including vaccination, once a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) has been declared by the WHO.

We as parliamentarians are guardians of the country’s hard-won freedoms, so we need to be aware of what is being negotiated and what sovereign rights are being negotiated away. The ACDP is deeply concerned that our sovereignty to decide on public health issues is being negotiated away. No wonder there is such a push back from African countries. The central question is whether after these amendments have been passed, could the WHO put South Africa under lockdown? Yes or no. If the answer is yes, then we have a problem.

Statement by ACDP DP WAYNE THRING: The ACDP believes that the proposed Pandemic Treaty read with the amendments to the International Health Regulations will set humanity into a new era that is strangely organised around pandemics: pre-pandemic, pandemic and inter-pandemic times. A new governance structure, under WHO auspices, will oversee the IHR amendments and related initiatives. It will rely on new funding requirements, including the WHO’s ability to demand additional funding and materials from countries and to run a supply network to support its work in health emergencies.

That is under article 12, which states that “in the event of a pandemic, real-time access by WHO to a minimum of 20% (10% as a donation and 10% at affordable prices to WHO) of the production of safe, efficacious and effective pandemic-related products for distribution based on public health risks and needs, with the understanding that each Party that has manufacturing facilities that produce pandemic-related products in its jurisdiction shall take all necessary steps to facilitate the export of such pandemic-related products, in accordance with timetables to be agreed between WHO and manufacturers.”

In addition, articles 15 and 16 will allow the WHO to require a state to provide resources,

“health products, technologies and knowhow” and to allow the WHO to deploy “personnel” into the country—that is, it will have control over entry across national borders for whoever it chooses. The WHO also repeats the requirement for the country to require the implementation of “medical countermeasures”—testing, vaccines, quarantine—on their population where the WHO demands it.

Furthermore, additional measures are proposed to limit freedom of speech such as contained in annexure 1, article 5(e) , relating to “Counter misinformation and disinformation”. Although freedom of speech is currently exclusively for national authorities to decide, and its restriction is generally seen as being negative and abusive, global institutions including the WHO have been advocating for censoring unofficial views in order to protect the people from what they call “information integrity”. This is unacceptable and in breach of our constitutional rights.

This issue goes to the heart of what Parliament is all about. It is about who is in charge. Are we, as a democratic Parliament, in charge of the laws of our country? Why are there no provisions for subjecting material amendments to international agreements to Parliamentary approval in terms of section 231(2)? Once we have given away these powers to the WHO, it is very difficult to get them back. No wonder there is a push-back from developing countries. Where is the process of finalising these amendments to the regulations?

WHO Member States continued negotiating on proposals to amend the International Health Regulations 2005), during the seventh meeting of the Working Group on Amendments to the IHR (WGIHR) was held on 5-9 February 2024.

To understand the far-reaching impact of these amendments one need only consider the statement by Dr Michael Ryan, Executive Director, WHO Health Emergencies Programme that, “This Working Group will define the next 10 years of global surveillance and of collective security when it comes to health emergencies and particularly high-impact epidemics (public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC).

Additional issues that are also being considered by the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB), which deal with equity, collaboration, capacity building and financing, will be addressed by Member States on 8 March 2024, when the seventh meeting of the WGIHR will resume. Proposed amendments to provisions related to governance, and foundational articles of the Regulations, will be addressed when the WGIHR meets for the eighth time in April 2024 to finalize the amendments.

The package of far-reaching amendments will be considered by the Seventy-seventh World Health Assembly in May 2024. If agreed to by consensus, they will be binding on all member states, including South Africa, without us as Parliamentarians playing any role in terms of section 231(2), or for that matter any oversight role in terms of section 55.

Developing countries have also expressed concerns that these negotiations were running parallel with the WHO pandemic treaty. A spokesperson for the Third World network said that “Several developing countries have said that the WHO has too many platforms for negotiations, and is simply not manageable”. Because there is no examination of the important decisions and advice that the WHO offered to the whole world, and the influence that major donors has on its decisions – it is all the more important to be very careful of giving up one sovereignty over public health issues.

What few people realise is that the scope of the proposed Pandemic Treaty and the IHR amendments is broader than pandemics, greatly expanding the scope under which a transfer of decision-making powers can be demanded by the WHO. Other environmental threats to health, such as changes in climate, can be declared emergencies at the director general’s discretion, if broad definitions of a One Health policy are adopted as recommended.

Concerns have also been expressed in other Parliaments. For example, this past December in a debate on the International Health Regulations 2005 in the UK parliament, the honourable Philip Davies warned that, “We are talking about a top-down approach to global public health hardwired into international law. At the top of that top-down approach we have our single source of truth on all things pandemic: the World Health Organisation’s director general, who it appears will have the sole authority to decide when and where these regulations will be deployed.”

The New Zealand government has appeared to have lodged a reservation to allow the incoming Government more time to consider whether the amendments are consistent with the national interest test required by New Zeeland law. The ACDP believes that South Africa should lodge a similar reservation given that elections are taking place in our country in the same month, May, when these far-reaching amendments are due to be considered by the World Health Assembly.

At the very least, the ACDP requests, no, demands an undertaking from government that it will not agree to any IHR amendments that would compromise South Africa’s ability to take domestic decisions on national public health measures even in the event of public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). In this regard, the ACDP has recorded its formal objections to the IHR amendments to the WHO.

Lastly, we recommend that section 231(2) be amended to allow us as parliament to reconsider international agreements that have been substantially amended, as is proposed in the case of the International Health Regulations.

I thank you.

Analysis and Recomendations

It was clear to me during the one hours and forty five minute debate that parliamentarians and the National Portfolio Committee on Health are unaware why there is a groundswell of robust international opposition to the IHR 2005 amendments, and the proposed new pandemic treaty.

It was also evident that Parliament is not being kept updated by the unelected representatives negotiating international treaties for South Africa at the WHO. The question, in a multilateral democracy, is why.

International agreements involve the minister for international relations and the justice minister, both of whom were not present at this WHO related debate last Friday. If they were not invited, this was a serious omission.

Significantly, this WHO focused debate in South Africa lead to the Deputy Minister for Health agreeing, on record, that the IHR 2005 amendments would go through a parliamentary approval process. It is unclear when.

The challenge is that this approval process may only happen after these two instruments are (potentially) voted in come May 2024, at the World Health Assembly, and potentially ratified at a later stage. I say potentially due to internal disagreement, member state push back and public resistance.

It is of critical importance that section 231(2) of the South African Constitution is urgently amended to firmly enable parliament to:

a) reconsider all significant international agreements that have been amended, as is the case of the International Health Regulations 2005, and

b) consider and approve or reject all new international treaties.Also critical in my view is Section 235 of the South African Constitution:

The Right to Self-determination: S. 235. The right of the South African people as a whole to self-determination, as manifested in this Constitution, does not preclude, within the framework of this right, recognition of the notion of the right of self-determination of any community sharing a common cultural and language heritage, within a territorial entity in the Republic or in any other way, determined by national legislation.All international agreements, as well as national laws, must go through an inclusive, robust and transparent public participation process as enshrined in the South African constitution. This includes reaching rural communities.

Foundationally, all WHO representatives for South Africa must be appointed only through a public consent and parliamentary approval process.

Continued membership in the WHO must be discussed at a multi-level structure in BRICS countries and between them, wherein allied countries can easily support each other where needed, during health issues of concern.

People Power Action

Read this key article from my other Substack platform, Take Back Power

Share, print and translate this WHO Withdrawal Bill drafted in South Africa

Sign this petition to demand S231 of South Africa’s Constitution is amended

Read this policy brief: Rejecting Monopoly Power over Global Public Health

Read this article on the U.N, WHO and sanctions for our non-compliance

Watch this show: Tedros’ role in the Ethiopian genocide + Kenya’s infertility

Part 2 in this series can be found here:

How did the South African government respond to the debate on the WHO facilitated corporate coup – a debate without public participation?

Shabnam Palesa Mohamed South Africa is the first African country to hold a parliamentary debate on the WHO facilitated amendments to the International Health Regulations 2005, and the proposed new pandemic treaty. On both, there has been no public participation process.

There should be no acceptance of any amendments. Giving one man the sole authority and right to dictate to the whole world and forcing countries to comply by instituting penalties and sanctions flies in the face of all human rights and freedom of choice and sovereignty